3 Reasons Cyber Security Needs Women

Cyber security is becoming an increasingly important topic for businesses everywhere. With cyber attacks happening on a daily basis, it is of the utmost importance to be on constant alert and have a comprehensive cyber security strategy in place. In other words – a unified approach to keeping the company assets safe in cyberspace. But how do women fit into the industry? We give you 3 reasons cyber security needs women.

In 2017 alone, we have seen numerous data breaches where the bad guys got a hold of a lot of sensitive information which had grave consequences in some instances. For example, in the Equifax credit reporting agency data such as Social Security numbers, birth dates, etc. on 143 million US citizens was stolen. The breach lasted from mid-May through July 2017 during which time hackers accessed people’s names, Social Security numbers, birth dates, addresses and, in some cases, driver’s license numbers. They also stole credit card numbers for about 209.000 people and dispute documents with personal identifying information for about 182.000 people. And they grabbed personal information of people in the UK and Canada, too.

Take this fact into account, as well: More US women than men have their identities stolen – a whole million more in 2014 alone! Moreover, women and girls are more likely than men to be targets of “remote sexual abuse” — coerced into posing nude online or being stalked through the Internet.

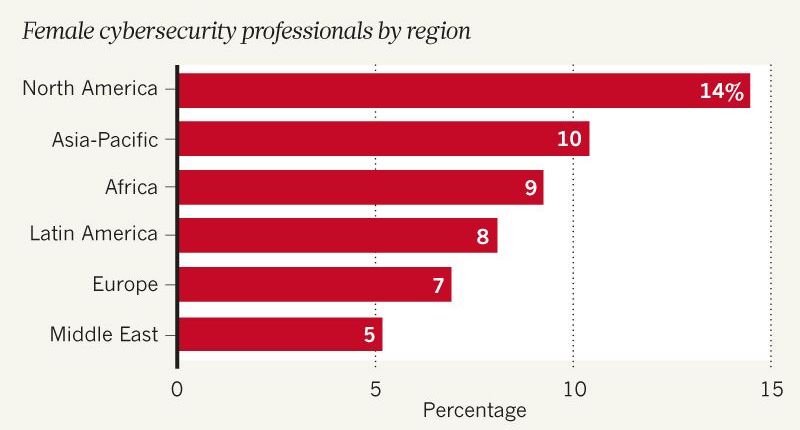

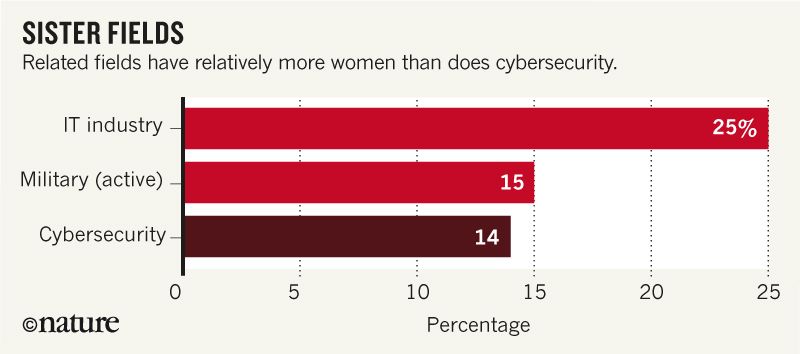

By the same token, if you take a look at the professionals working in the cyber security field – those who protect databases, software systems and computer networks from access, change or destruction – a big majority of them is male. Only 11% of them are women worldwide and only 14% in North America, which doesn’t really make sense if as much as 57% of the US professional workforce is comprised of women. Even cyber security’s sister industries do better: 15% of the US military and 25% of staff in information technology are women. By 2020, 2 million more cybersecurity jobs will be needed worldwide in addition to the 3.2 million people who are already employed in the field, of whom almost 750.000 are in the United States.

Reason #1: Women have been in cyber security for a century already

However, due to the historical and social circumstances, their achievements have been pushed aside while those of their male colleagues have been made famous, to say the least.

During World War II, 10.000 women in the US worked as “code girls” on deciphering encrypted messages sent by the Germans and the Japanese. Over the pond was no different – 7.000 women worked in the now famous Bletchley Park – the UK center for cryptanalysis – making up to 75% of the workforce on the premises. Even one of the biggest Hollywood stars of the time, Hedy Lamarr made her contribution by patenting an encryption method for signaling to torpedoes, which served as a basis for WiFi, GPS and Bluetooth technologies as we know them today.

Another woman, Elizebeth Smith Friedman, was one of the inventors of the cryptography science for the FBI. Her techniques in the 1940s broke international spy rings, decoded 3 Nazi Enigma machines and contributed to the early work of the forerunner to the CIA. However, after the war, her elite code-breaking unit was shut down and various men took credit for her work, including her husband William Friedman and FBI director J. Edgar Hoover.

Katherine Coleman Goble Johnson

Furthermore, women were the first programmers, calculating weapons trajectories by hand and entering them into the Electronic Numerical Integrator and Computer (ENIAC) at the University of Pennsylvania, in the 1940s. In fact, the term “computer” originally referred not to the machine but to the women who programmed it. Other women developed the first programming languages, methods to detect intrusions into computer systems and network bridges between communication centers. In the 1950s, African American female mathematicians at NASA calculated the aeronautical trajectories that put men on the Moon, most notably Katherine Johnson.

The proportion of women in computer science grew until the mid-1980s – the dawn of personal computing – when numbers dropped abruptly. Today, only around 18% of US computer-science majors are women, compared with around 37% in 1984. Even so, in the past decade, women have held influential positions in US national cyber security:

- Theresa Payton was the first female chief information officer in the White House, under former president George W. Bush.

- Melissa Hathaway was appointed by former president Barack Obama in 2009 as his first ‘cyber czar’, in the role of acting senior director for cyberspace for the National Security Council.

- Letitia Long was the first woman to head a major US intelligence agency, as director of the National Geospatial-Intelligence Agency from 2010 to 2014. This supplied the satellite, geographical and social-media data that enabled Osama bin Laden’s capture.

- Janet Napolitano headed the Department of Homeland Security (DHS) from 2009 to 2013, and Kirstjen Nielsen has been at the helm since 2017.

- Jeanette Manfra, the chief cybersecurity official for the DHS, is leading the investigation into Russian hacking of US voter registration rolls before the 2016 presidential election.

There are also women who are taking more underground roles — as cyber spies:

- Former judge Shannen Rossmiller gathered global online intelligence for the FBI after the terrorist attacks of 11 September 2001. By posing as male militants from Iraq and Afghanistan in extremist chat rooms, she exposed weapon caches, bomb plots and terror cells in more than 200 operations.

- Cyber sleuths like Kimberly Ritter are fighting crimes such as online sex trafficking. Ritter’s work inspired computer scientists to develop an app called Traffickcam that enables the public to upload photographs of hotel rooms to a database. By matching these to images in advertisements for escorts, law enforcement agencies can improve the way they track down victims and their traffickers.

Reason #2: Women tend to be more educated than men in the industry

Even though they are outnumbered their male counterparts, female candidates for cyber security jobs are usually more educated. Women professionals are more likely to have a master’s degree or higher (51% for women globally, compared to 45% of men), while also bringing wider expertise. Although both female and male employees train extensively in computer science, information and engineering, women’s degrees are more likely to come from fields such as business, mathematics and social science (44% for women, compared with 30% for men).

Jobs in the cyber security industry require diverse skills as professionals must understand network security, risk mitigation and information protection, and be prepared for future activities in artificial intelligence, machine learning and virtual-reality mapping. They need to manage projects, navigate legal and compliance codes, and work in sectors from health care to law enforcement. And yet training beyond fields in science, technology, engineering and math (STEM) is not generally rewarded because most cyber security employers view computer science or engineering backgrounds as a priority when hiring.

But, some big tech companies are changing their outlook. In 2011, Microsoft co-founder Bill Gates undervalued liberal-arts education. Now, the company’s president Brad Smith argues that such training is crucial for the future of computing, especially artificial intelligence. Google executives were shocked after they analyzed their workforce data and found that STEM expertise was the least important factor associated with employees’ success. Instead, qualities such as being a good coach, problem-solver or critical thinker ranked higher.

Reason #3: Women are more often victims of cyber crime

Women are in the position to offer unique insights into the mechanisms of cyber crime finding themselves on the receiving end of it far more often than men. In the US, women were 26% more likely than men to experience identity theft in 2008, often involving the fraudulent use of a bank account or credit card – with over 60% of the victims losing their money. On average, women also took longer than men to notice the breach: 83 vs. 45 days. This is partly because men are more likely to bank and shop online, and so receive automatic notifications within hours – much faster than the weeks it can take to spot unauthorized transactions on monthly financial statements.

Moreover, there are cyber crimes such as “sextortion”, which are specifically directed at women and girls. Criminals trick their targets, using e-mails infected with software viruses, for instance, to gain access to their computers. (For more information on various types of malware, take a look at our infographic.) Perpetrators can search for photos on hard drives or use webcams to watch women and girls after which they blackmail targets by threatening to post images and videos on (child) pornography websites, to compel further sexual activity. The extortion can extend for years, because images can be permanently installed on multiple platforms and one perpetrator might have hundreds of targets.

Even though strangers are usually assumed to be responsible, it is women’s spouses, boyfriends or family members that often initiate security breaches. Abusers acquire passwords through key-logging devices or by coercing their targets to hand over passwords. Not only that, but misuse of technology online is linked to physical abuse offline. In a national survey, 97% of US domestic abuse shelters reported that their female clients had been harassed through technology.

At the end of the day, it is clear that cyber security’s future depends on its ability to attract, retain and promote women, who represent a highly skilled and under-tapped resource. The industry also needs to learn about women’s experiences as victims of cyber crime and the steps needed to address the imbalance of harm. Security systems must protect everyone, equally.